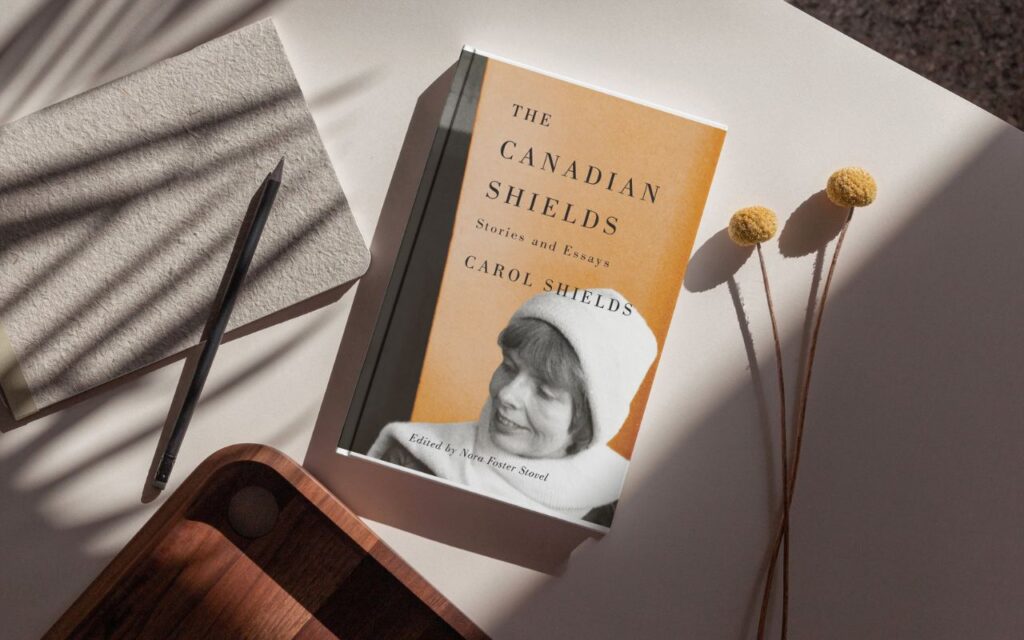

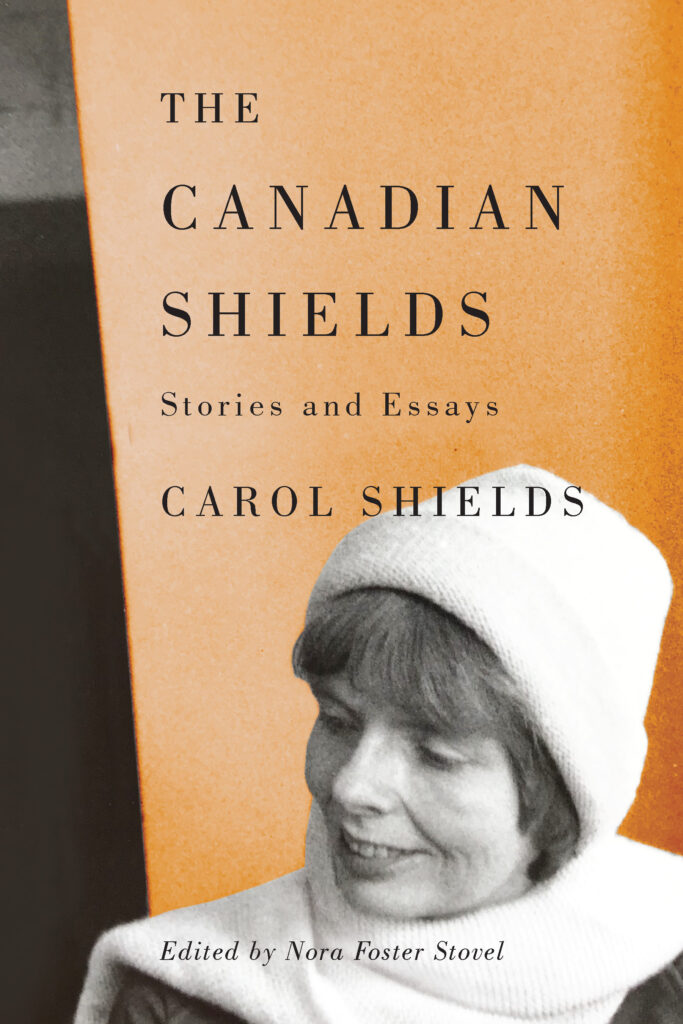

Love Carol Shields? You’ll want to know about this brand new collection of her work

Books15.11.2024

It’s been an exciting fall for those of us who are fans of Carol Shields — the award-winning novelist, short story writer, essayist, playwright, and poet.

Thanks to literary scholar Nora Foster Stovel, we now have access to more than two dozen previously unpublished short stories and essays by Shields. Stovel’s latest book —The Canadian Shields: Stories and Essays, which was published by the University of Manitoba Press in early September—contains 50 literary treasures. (It also contains two dozen additional essays by Shields that had been published but never collected.)

I found myself making pages and pages of notes while I was making my way through this collection. I kept stumbling upon passages I knew I’d want to return to again and again. Shields has so many noteworthy things to say about reading, writing, and the value of women’s stories.

Shields recalls, for example, the magical moment when she first fell in love with the act of reading, while sounding out the words in a primary school reader. She tells us that Dick and Jane — the characters in those books — “were the key that opened the door into the world of reading”, and that, “for writers, learning to read is, I think, the prime spiritual experience of childhood.”

She also writes about how this love affair with reading continued throughout her life: “I would like to make the case today for solitary time, for a life with space enough to curl up with a book,” she notes in one essay. “We use the expression, ‘being lost in a book,’ but [when we’re reading] we are really closer to a state of being found.”

Shields repeatedly emphasizes the importance of women’s stories. She recalls a time when books written by women were either ignored or treated dismissively, recalling how one 1970’s-era novel about motherhood was described by a reviewer as “a diaper novel.”

She talks about how that attitude began to change as the women’s liberation movement gained power and women began to seek out the stories of other women — both through conversation and on the page: “We think of the women’s movement as an epic of demonstrations and marches and consciousness-raising groups, but it was also an era in which women could read about the real life of women,” she notes. “No wonder women’s books became a refuge for women readers. There they found themselves; they could be themselves. There they felt the distance shrink between what was privately felt and universally known. Women, I think, were hungry for their own honesty — they’d talked about it (women have always talked), but they needed to see it written down.”

She describes her own fascination with ordinary moments and ordinary lives: “Human activity with its random jets of possibility and immobilization was the oxygen I sought. The hum of human busyness engaged me at every level; it was what illuminated my imagination and found its way into my novels.”

It’s hard to do justice to a book like this in a short review. It’s a point Shields herself made in one of the essays in this collection — the challenges a reviewer faces when writing a book review. “The actual writing of the review is clearly an absurd reduction. The complex has to be made simple. A reviewer must, in a column or two of print, convey to the reader the essence of a book which took its author three years or six years or twenty years to write.” Or, in this case, even longer than that.

Shields argues that books like hers that capture the reality of women’s lives will always find an audience of enthusiastic readers. “There really is a network of women readers — ask publishers — in which one woman says to another, or to ten others, ‘There’s this book you’ve just got to read.’”

In other words, a book like this one.