Representation remains the key to powering up women in tech

Career03.03.2025

When Kathryn Reilander entered the Electrical Engineering Technician program at Algonquin College in 1998, she didn’t just stand out – she was one of only two women in the room.

“I remember they wrote an article about me in 1999 because I was one of the only women there,” she laughed. “While there’s still an old-school thinking of ‘These are careers for women and these are careers for men,’ the lines are definitely blurring.”

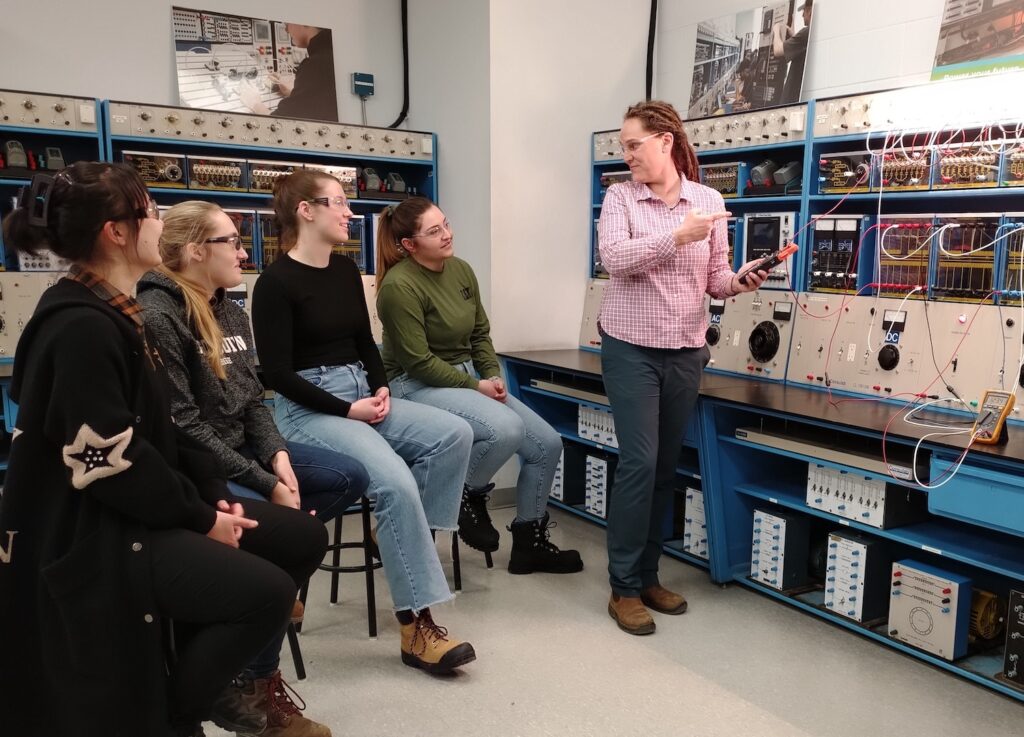

Now, on the other side of the classroom, as a leader in engineering and tech education, she’s not just thriving in a traditionally male-dominated industry, she’s working to make sure more women can do the same.

“One of the biggest challenges is that women don’t see themselves in these jobs,” said Reilander. “We need to start changing their minds by showing them all the cool possibilities that are out there.”

More women, more visibility

Today, while women in tech still make up a small percentage of the workforce, their numbers are growing.

In recent years, we’ve seen an increase in dedicated efforts to close the gender gap across small businesses, large public and private organizations, as well as all levels of education. From mentorship programs to investment in leadership development, great strides have been taken to increase representation, and support women from the moment they begin their learning and career journeys.

At Algonquin College, for example, where Reilander now teaches and coordinates the Electrical Engineering Technology program, faculty proactively conduct outreach. As soon as students enroll, if they are women, non-binary, or trans they get that added reassurance that they are welcome and belong in the program.

“When I was in school, there were no women educators…, no one that looked like me,” said Reilander. “As a student, I really tried to advocate for myself. I spoke up for myself and was good at communicating, so that allowed me to be a prominent voice in the classroom. That’s not always the case for women in these programs.”

Even today, she says it’s not uncommon for women to feel left out in the classroom, especially when it comes to group or partner projects. Reilander says the faculty make a conscious effort to connect the women across the engineering and tech programs to help alleviate any feelings of isolation.

“It’s about making sure they feel welcome from Day 1,” she explained. “If they don’t make a connection in the first two weeks, they’re more likely to drop out. We make sure that connection happens.”

Breaking down barriers, changing perceptions

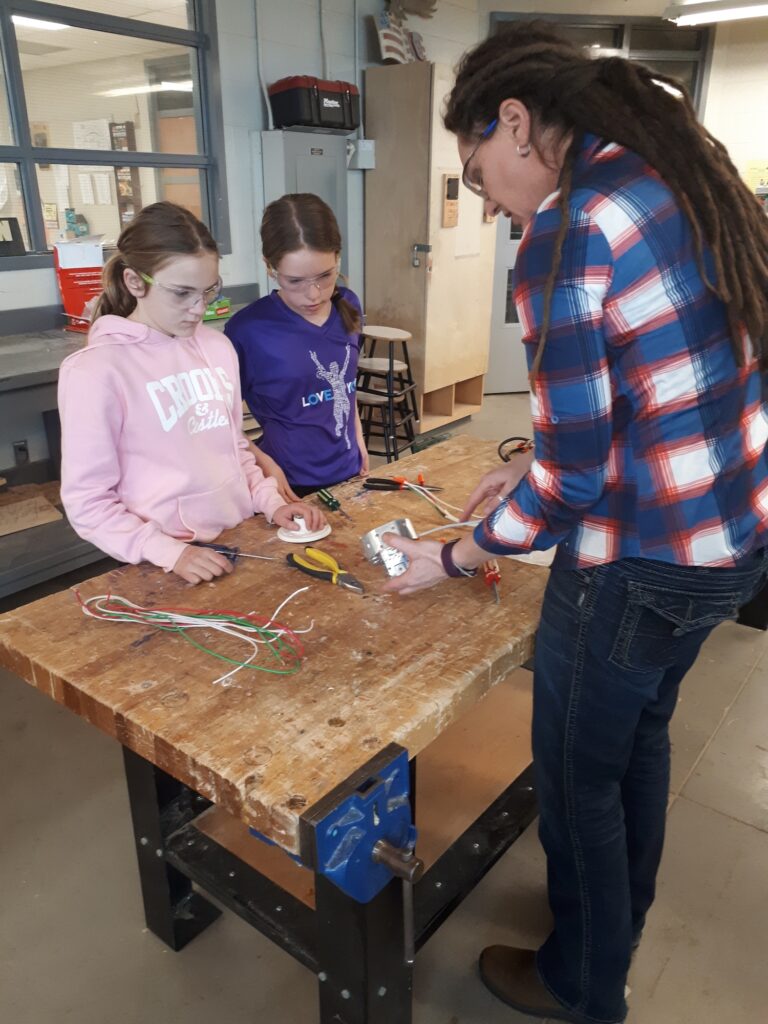

While the support systems in schools are now stronger, Reilander believes the next big challenge is getting more young women to see these career paths as viable, rewarding and lucrative options in the first place.

“We need to change the way we talk about math and science in high school,” she said, stressing that all too often girls write off these subjects because they don’t see where they could lead.

“They don’t know that there’s a middle ground between being an engineer in an office and working in the trades,” she added. “Technician and technologist roles are dynamic and hands-on, but many young women have never even heard of them.”

Social perceptions play a role, too.

“In Grade 7 or 8, kids want to fit in. They don’t always see math or science as ‘cool,’” Reilander said. “We need to shift that message. We need to show them women in these careers who are thriving, who love what they do.”

The power of representation

Reilander has seen firsthand how much of a difference representation makes.

“When a woman student walks into a classroom and sees a woman teaching the course, it sends a message: I’ve done it, and you can too,” she said.

The goal isn’t just to get more women into these fields – it’s to reach the tipping point where their voices are truly heard. Research suggests that once women make up at least 30 per cent of a group, their ideas are more likely to be recognized, innovation increases, and the workplace culture starts to shift.

“That’s where we need to get,” Reilander said. “And we’re on our way, but it can be a slow process taking generations.”

As she approaches her 16th year as a program coordinator at the college, Reilander is encouraged to see an increase in the number of young women joining tech programs.

But she remains steadfast in her message: Don’t count yourself out. Math, science, engineering – these fields are for you.